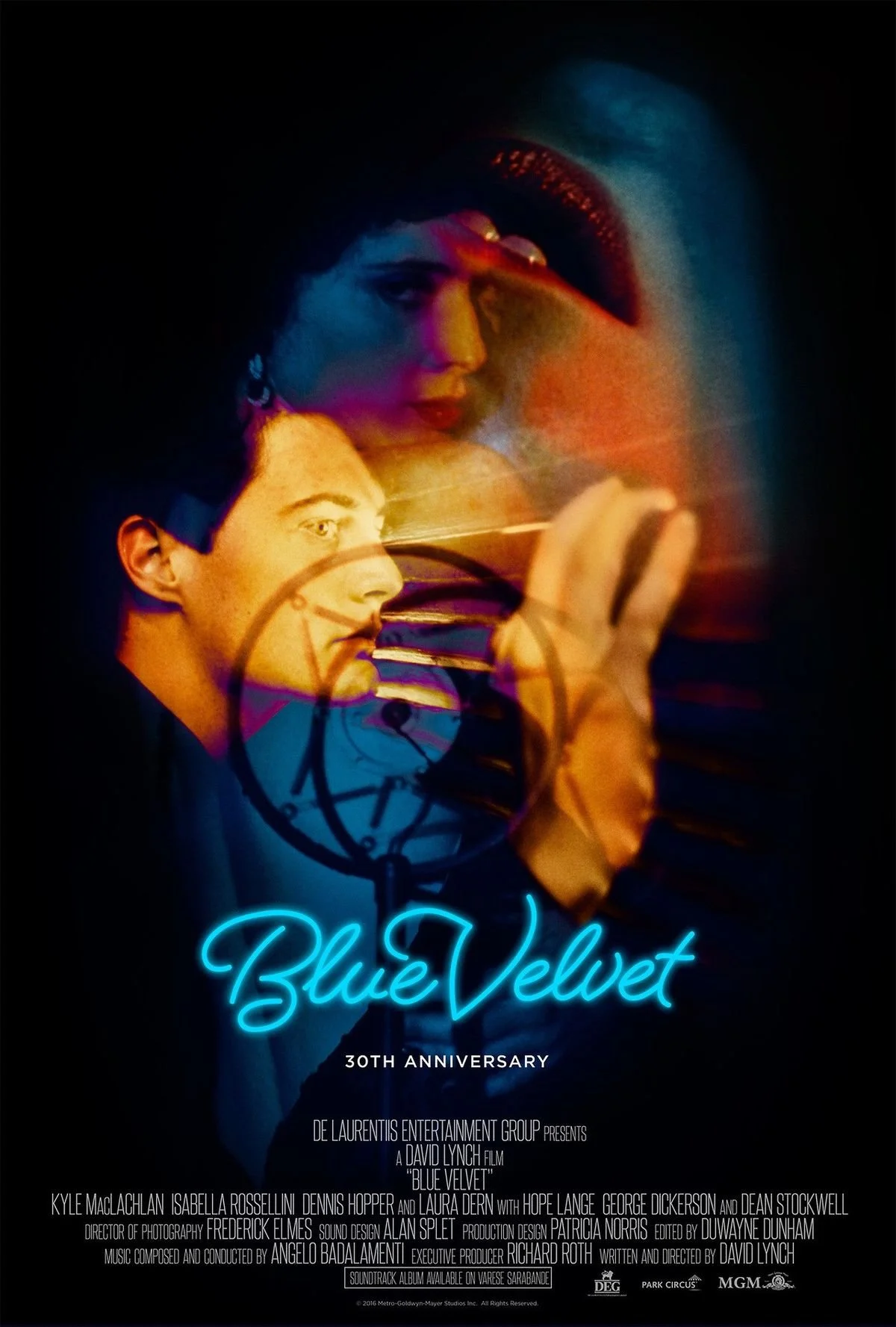

Blue Velvet a Descent into Suburban Nightmares

David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, released in 1986, is less a film than an unsettling experiment in the American psyche, a celluloid labyrinth where the familiar becomes uncanny and the ordinary pulses with menace. In Lynch’s hands, the small town of Lumberton is not a backdrop, but a membrane, a thin, fragile surface stretched over primordial urges and unspeakable violence.

The film’s genre alchemy, a volatile blend of noir, psychological thriller, horror, and surrealism, serves not simply to disturb, but to interrogate the stories we tell ourselves about innocence, community, and the hidden terrors that shape both.

The film opens in the quaint town of Lumberton, where Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan), a college student, returns home after his father suffers a stroke. One day, while walking through a field, Jeffrey discovers a severed human ear. This gruesome discovery leads him to team up with Sandy (Laura Dern), the daughter of a local police detective. Their investigation soon leads to Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini), a torch singer trapped in a violent and abusive relationship with Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper), a psychotic criminal who embodies raw, unhinged evil.

Jeffrey’s descent into Dorothy and Frank’s fractured world is not merely a narrative turn, but a philosophical experiment, an exploration of what happens when the membrane between ‘normality’ and chaos ruptures. The discovery of the ear is not just an inciting incident; it is an invitation to cross thresholds, to peer into the abyss where desire, violence, and ambiguity churn together.

Blue Velvet is obsessed with the duality of American life, the mythic, sunlit suburbia of manicured lawns and picket fences, and the writhing, insectile chaos beneath. Its iconic opening sequence, roses in bloom, a white fence, children shepherded across the street, evokes a cultural mythology as much as a place. Yet the camera soon burrows into darkness, exposing the beetles beneath the grass, a vivid allegory for the shadow truths that underwrite every utopia.

Voyeurism in Blue Velvet is not simply a plot device, but a philosophical lens. Jeffrey’s passage from observer to participant is emblematic of a deeper human tension between the urge to know and the danger of knowing too much. Lynch’s camera implicates the viewer, asking whether the act of watching is itself a moral trespass and whether desire can ever be disentangled from transgression.

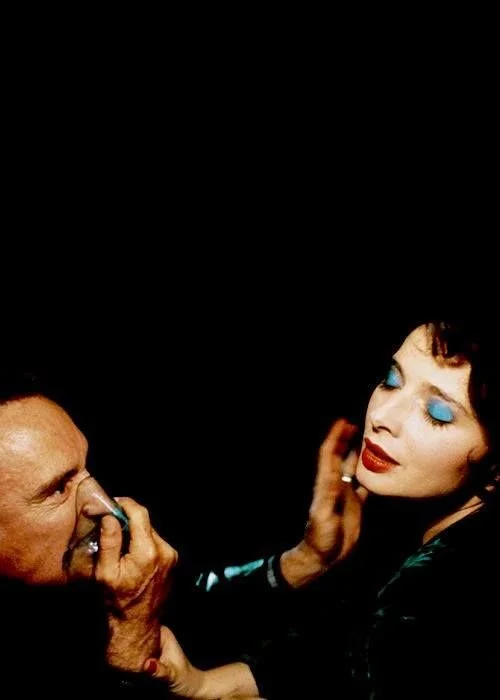

The film’s sexual politics are fraught and ambiguous. Dorothy, caught in the gravitational field of Frank Booth’s sadism and Jeffrey’s curiosity, oscillates between victimhood and agency, trauma and a kind of shattered strength. Rossellini’s performance is a study in paradox: she is at once exposed and inscrutable, inviting both empathy and discomfort. In Blue Velvet, power is never simple; it is always contested, always refracted through the lens of pain.

Dennis Hopper as Frank Booth delivers one of the most terrifying performances in cinema history. Frank is a chaotic force, infantile, sadistic, sexually confused, and violently unstable. His use of amyl nitrate (inhaled from a gas mask) and his chillingly disjointed speech (“Mommy!” “Daddy!” “Let’s f***!”) turn every scene he’s in into a waking nightmare.

Isabella Rossellini as Dorothy Vallens gives a raw, fearless performance. She is both seductive and deeply wounded, evoking empathy and discomfort in equal measure.

Kyle MacLachlan as Jeffrey provides a perfect conduit for the audience. His boyish charm and curious nature make him a convincing everyman, but his moral compass becomes increasingly compromised, highlighting the complexity of human nature.

Laura Dern as Sandy serves as a beacon of normalcy and hope, yet her relationship with Jeffrey is tinged with unease, especially when she learns of his descent into Dorothy's world.

Blue Velvet is a film of striking visual contrasts. Cinematographer Frederick Elmes crafts images that are simultaneously beautiful and menacing. The lighting, especially in Dorothy’s apartment, is shadowy and expressionistic, evoking the chiaroscuro of film noir. Meanwhile, the town of Lumberton is bathed in soft, pastel tones, emphasizing the uncanny disparity between surface and substance.

The sound design is equally masterful. Angelo Badalamenti’s score , lush, romantic, and ominous , becomes an essential part of the film’s emotional texture. Songs like Bobby Vinton’s “Blue Velvet” and Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams” are used ironically, infusing moments of terror with nostalgic sweetness.

Lynch’s directorial approach is closer to dream logic than narrative convention. Long takes, abrupt juxtapositions, and moments of surreal rupture accumulate into an atmosphere of unease. Blue Velvet is less a story than a waking nightmare, a fractured fairy tale where beauty and horror are inseparable, and where the slow, deliberate pacing forces the viewer to linger in discomfort.

Moral clarity is not on offer. Instead, Lynch confronts us with the impossibility of neat conclusions, inviting reflection rather than resolution. Blue Velvet becomes a meditation on the coexistence of innocence and depravity, and on the ways we are all haunted by what we cannot, or will not, see.

Upon release, Blue Velvet polarised critics and audiences. Some praised it as a bold work of art, while others decried it as misogynistic or exploitative , particularly due to the sexual violence inflicted on Dorothy. Over time, however, it has come to be recognized as a landmark of American cinema.

Its influence is vast, shaping the tone and style of later works like Twin Peaks, Mulholland Drive, and countless neo-noirs and psychological thrillers. The film’s subversion of 1950s nostalgia, its postmodern blending of genres, and its fearless excavation of the unconscious mind have made it essential viewing for serious cinephiles.

Blue Velvet is not an easy film to watch , nor is it meant to be. It is disturbing, provocative, and often grotesque. Yet it is also lyrical, poignant, and fiercely original. By peeling back the layers of suburban life to reveal the grotesque beneath, Lynch forces viewers to confront the uncomfortable truths about society, sexuality, and themselves.

It remains one of Lynch’s most vital works and a towering achievement in American cinema.

By Jake James Beach

Founder of The Deep Dive Society

If you’ve enjoyed this exploration, we’d love to welcome you back to the Deep Dive Society. Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media to stay connected, join the conversation and help build a community dedicated to curiosity, reflection and the art of looking deeper. Together, we can shape a society committed to the Deep Dive mission.