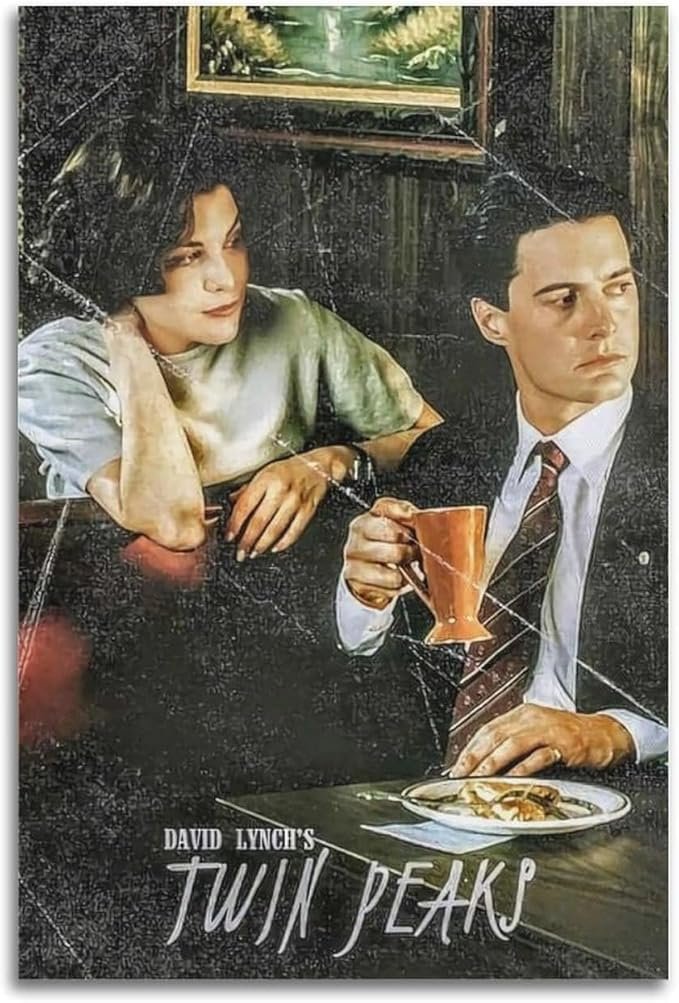

David Lynch: Architect of Dreams, Master of the Uncanny

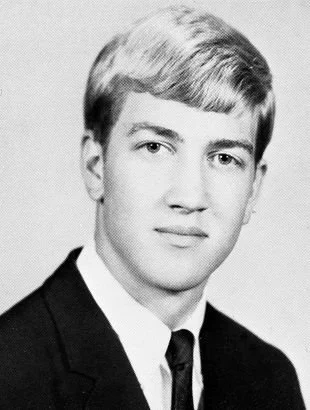

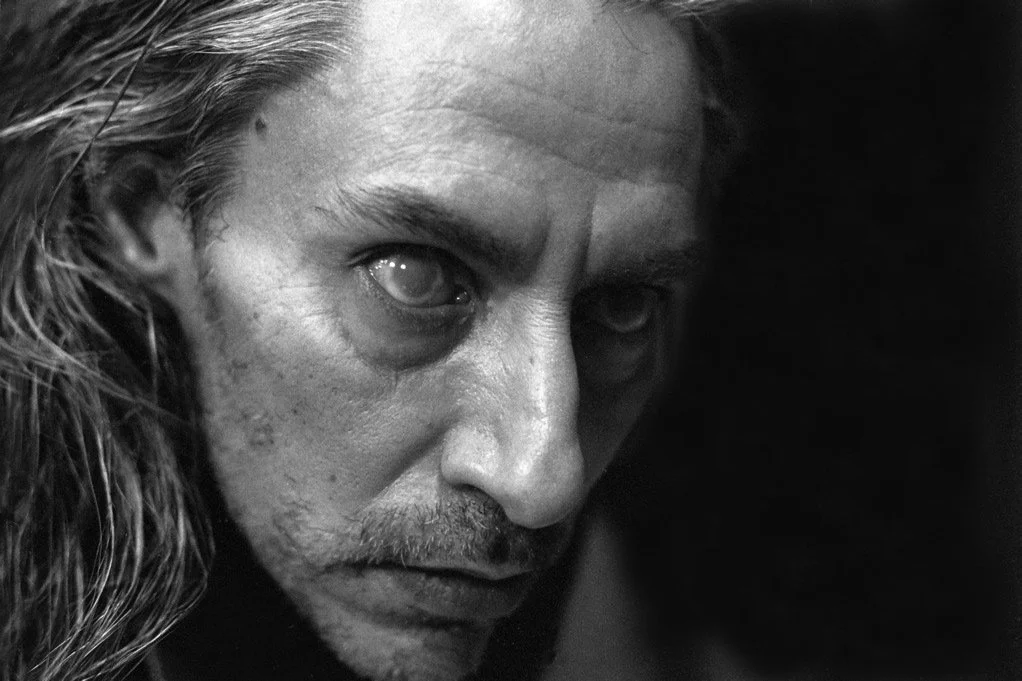

David Lynch. Photograph: Chris Saunders

“The eye of the duck is a scene that’s essential. Without it, the duck’s not a duck.”

David Lynch

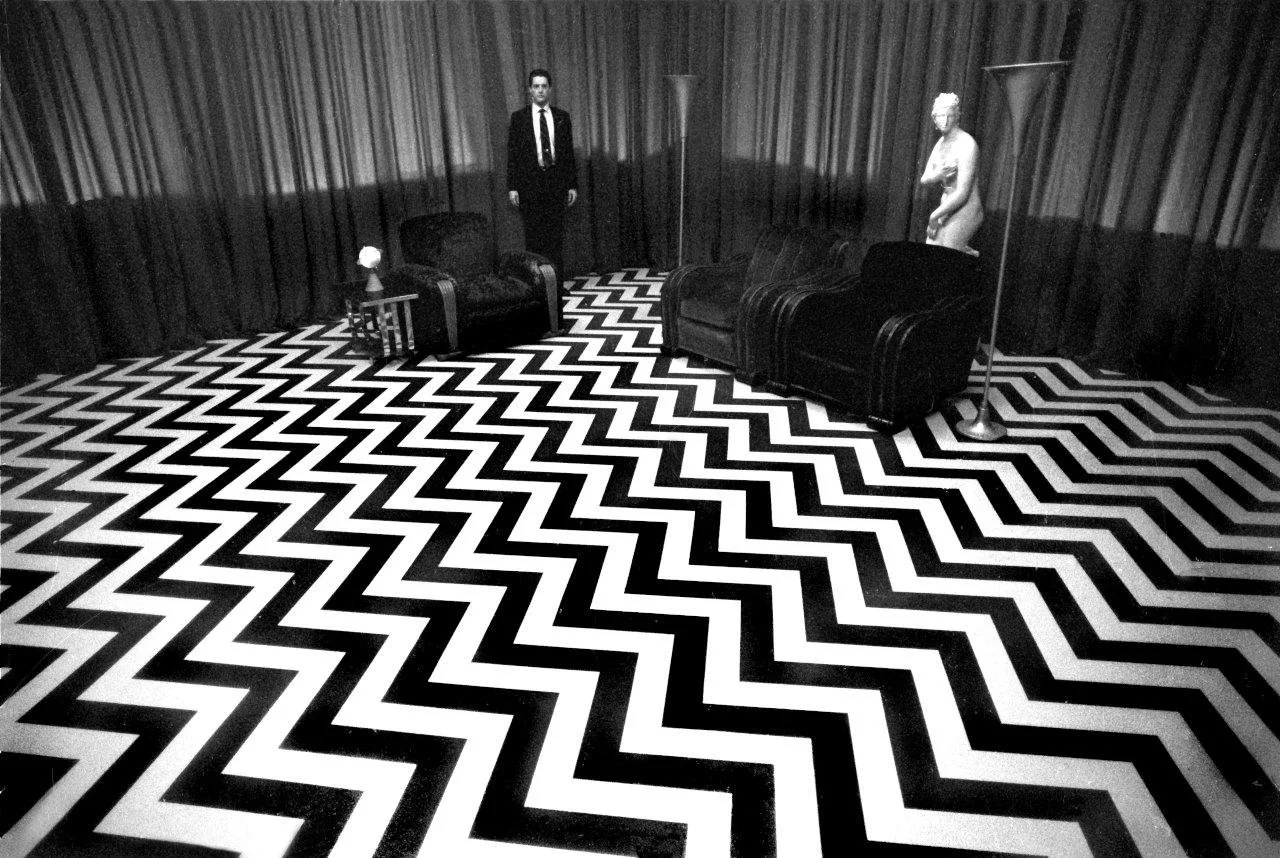

In the vast and varied pantheon of cinema’s most daring visionaries, David Lynch stands alone as a genre unto himself. His films do not simply tell stories, they absorb, disorient, and recompose the viewer. Lynch creates atmospheres rather than plots, emotional textures rather than tidy resolutions. Whether guiding us through the shimmering nightmare of Mulholland Drive, inviting us into the red curtained purgatory of Twin Peaks, or dragging us through the industrial shadows of Eraserhead, he shapes cinematic experiences that break form and expectation.

To watch Lynch is not simply to observe; it is to inhabit. You step into his spaces as if entering a dream, uncanny, alluring, and tinged with dread. You don’t walk away with answers, you walk away with impressions, with images that cling like residue. Love him, fear him, or remain perpetually baffled by him, there is no denying that Lynch altered the language of film, expanding what cinema is allowed to be.

From Canvas to Camera, Lynch’s Early Years

Born in Missoula, Montana in 1946, Lynch spent his childhood in various small American towns, a drifting upbringing that would later permeate his work with the paradoxical mix of wholesome familiarity and lurking menace. These were places where front lawns were manicured and neighbors smiled politely, yet something, an invisible vibration beneath the surface, felt off kilter. Lynch has always said he finds “darkness in the most beautiful places,” and his childhood environment became the blueprint for that contrast.

Before he ever picked up a film camera, Lynch envisioned a future as a painter. At the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, he immersed himself in the physicality of paint, its textures, thickness, and ability to distort or reveal. This visual sensitivity underpins all of his cinema, every frame feels constructed with the careful consideration of a canvas.

It was during this period that Lynch had a strange idea, a painting that moved. That impulse became The Alphabet (1968), an unsettling animated short blending nightmares, abstraction, and bodily anxiety. The film attracted the attention of the American Film Institute, opening the door to his life as a filmmaker. But Lynch never stopped painting. His gallery work, filled with raw textures, grotesque forms, and dark humor, reflects the same sensibilities as his movies, childlike wonder fused with existential dread.

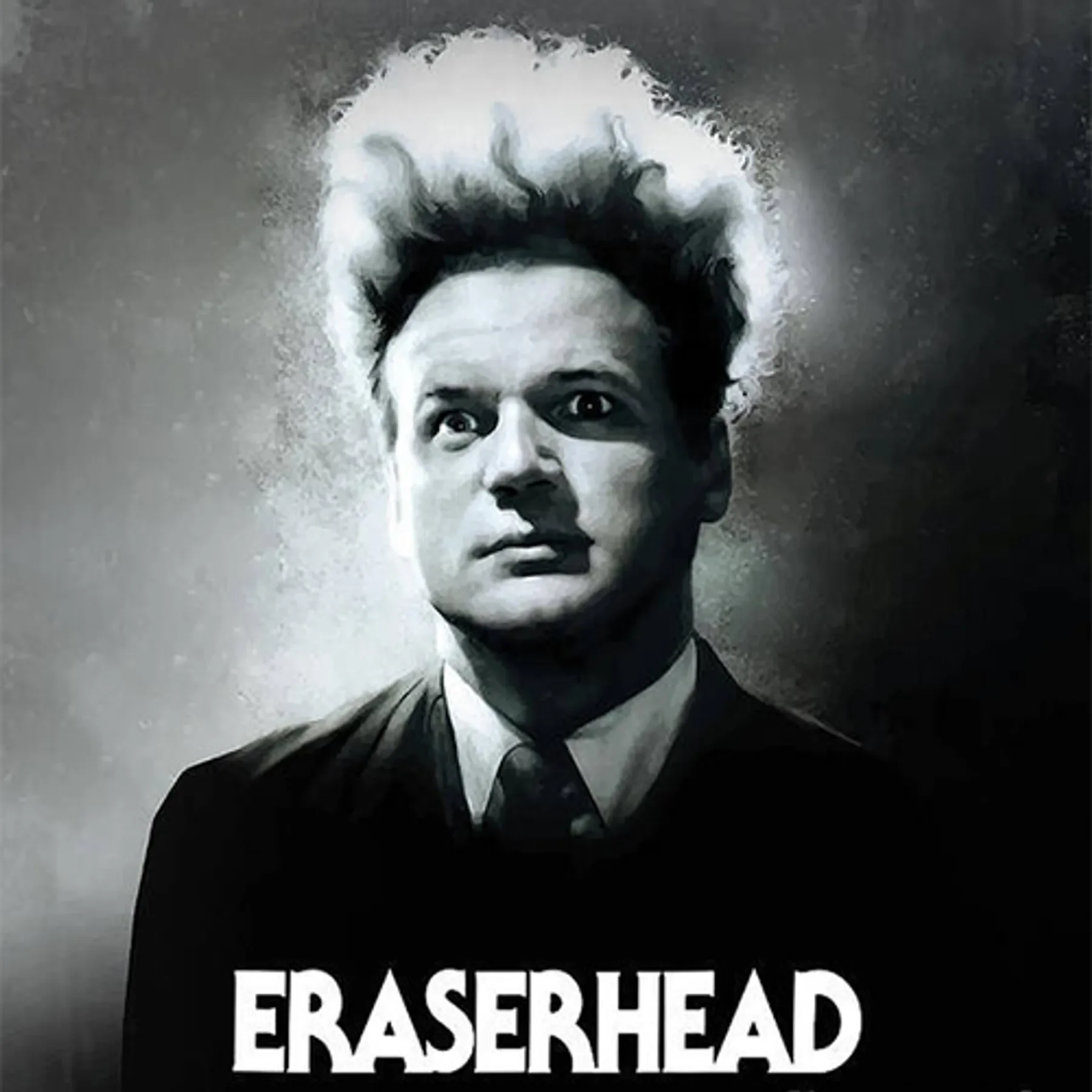

Eraserhead (1977), A Nightmare Realised

Filmed over five gruelling years with a crew that was equal parts dedicated and delirious, Eraserhead emerged as something wholly new in the cinematic landscape, a film that refused interpretation but demanded attention. The story centres on Henry Spencer, a trembling figure navigating industrial wastelands and monstrous parenthood, though “story” feels like too clean a word.

Is it about fatherhood anxiety? The collapse of industrial society? The terror of the body? Or simply a dream from which the dreamer refuses to wake?

Whatever it is, Eraserhead announced the arrival of a filmmaker who didn’t merely depict nightmares, he constructed them with a meticulous, almost spiritual devotion. Its soundscape, crafted with composer Alan Splet, remains one of the most influential in film history, turning noise itself into an emotional weapon.

Hollywood noticed. Suddenly, Lynch was no longer the art school oddity who made that bizarre student film. He was a visionary.

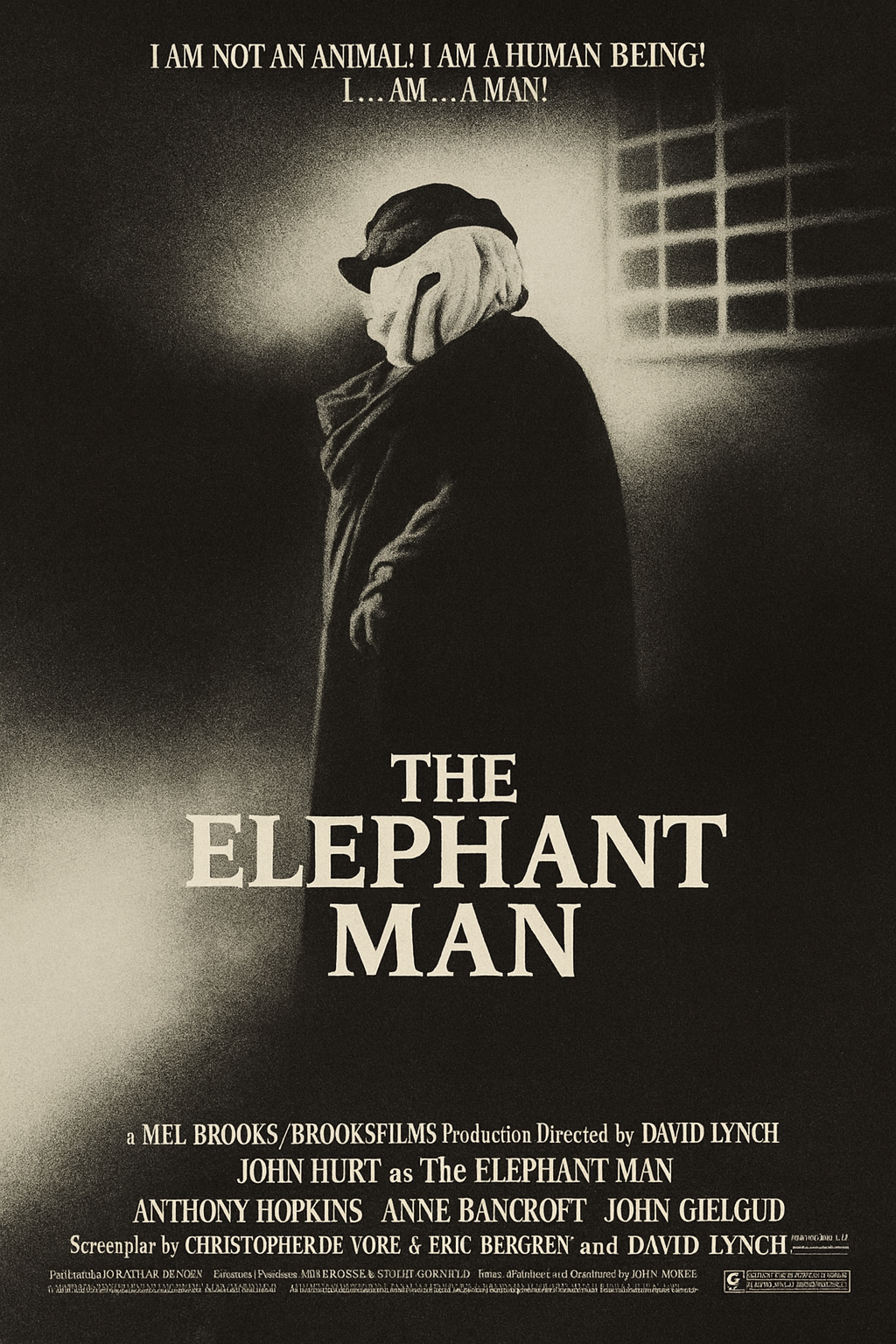

Breakthrough and Stumbles, The Elephant Man and Dune

Following the success of Eraserhead, Lynch was handed an unexpected opportunity, a biographical period drama produced by Mel Brooks. The result, The Elephant Man (1980), was a tender, deeply humane film that showcased his ability to balance surreal aesthetics with emotional sincerity. Shot in luminous black and white, it earned eight Academy Award nominations, instantly elevating Lynch to the ranks of major filmmaking talents.

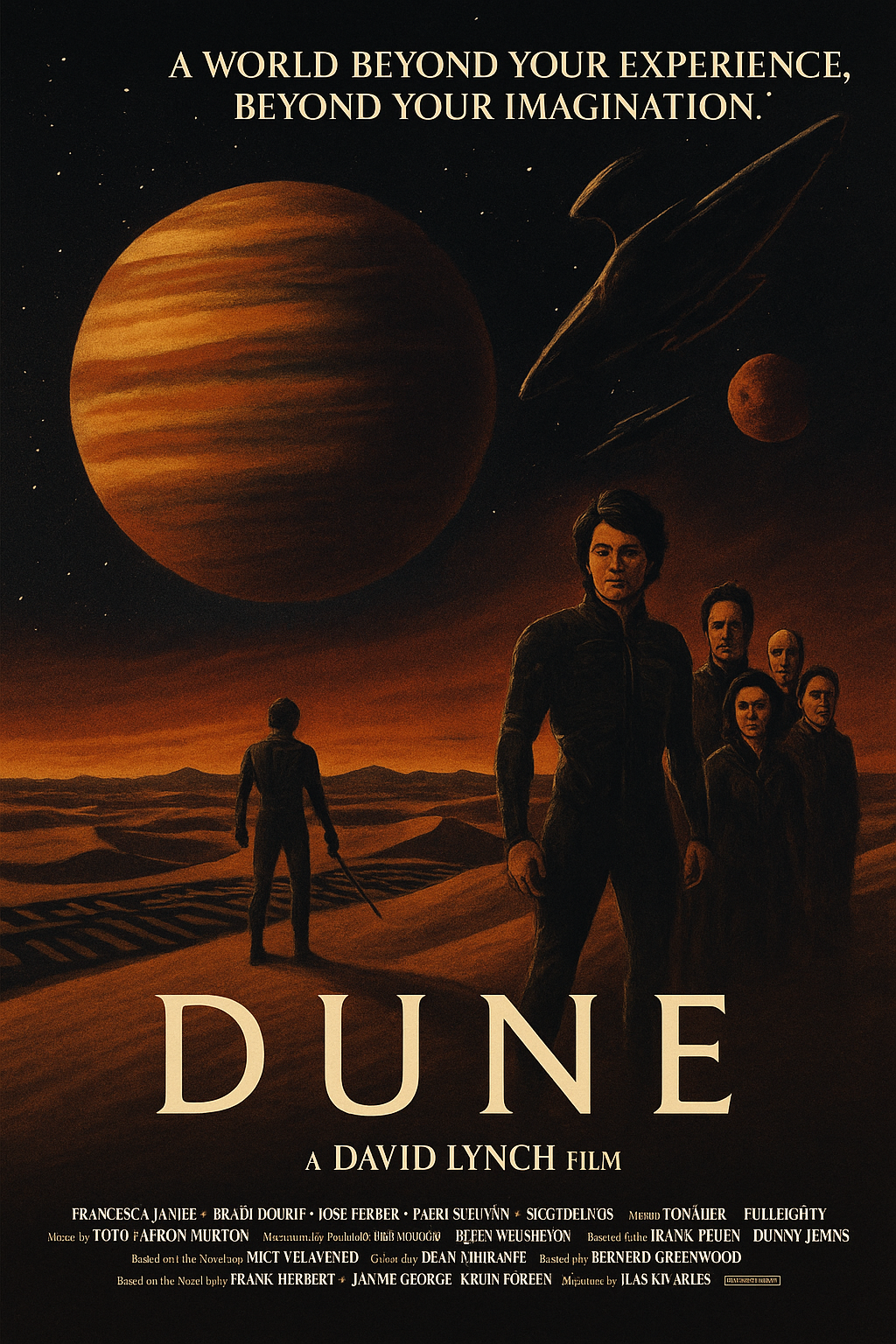

Then came Dune (1984). The studio wanted a blockbuster. Lynch wanted a cosmic fever dream. Neither got what they hoped for.

Riddled with studio cuts and narrative compromises, Dune remains his most disowned work, a film he won’t discuss in detail and refuses to recut. Yet even within its disarray, one sees traces of Lynch’s visual ambition, baroque designs, grotesque villains, moments of startling beauty. It was a misfire, yes, but a fascinating one.

Twin Peaks and the Television Revolution

In 1990, Lynch and co creator Mark Frost unleashed Twin Peaks, a show so strange and hypnotic that it felt like an alien broadcast smuggled onto network television. Its question, Who killed Laura Palmer?, became a national obsession.

But Twin Peaks was never just a mystery. It was a meditation on grief, trauma, identity, and the supernatural currents humming beneath small town life. Mixing soap opera melodrama with surreal dream logic, it pushed the boundaries of what TV could be long before prestige television became the norm.

Cancelled after two seasons, it might have faded into cult memory, until Twin Peaks, The Return (2017). This 18 hour opus wasn’t a revival, it was a revolution. Episode 8 in particular, an atomic explosion turned metaphysical poem, remains one of the most audacious pieces of television ever made.

Twin Peaks, Fire Walk With Me and Twin Peaks, The Return

Twin Peaks, Fire Walk With Me and Twin Peaks, The Return stand as two of David Lynch’s most daring and emotionally devastating works, each reframing the mythology of Twin Peaks in radically different ways. Though separated by twenty five years, the two pieces operate in dialogue, shaping a haunting meditation on trauma, identity, and the cyclical nature of evil. Together, they elevate the Twin Peaks universe from cult television to a singular, multi decade exploration of the human soul.

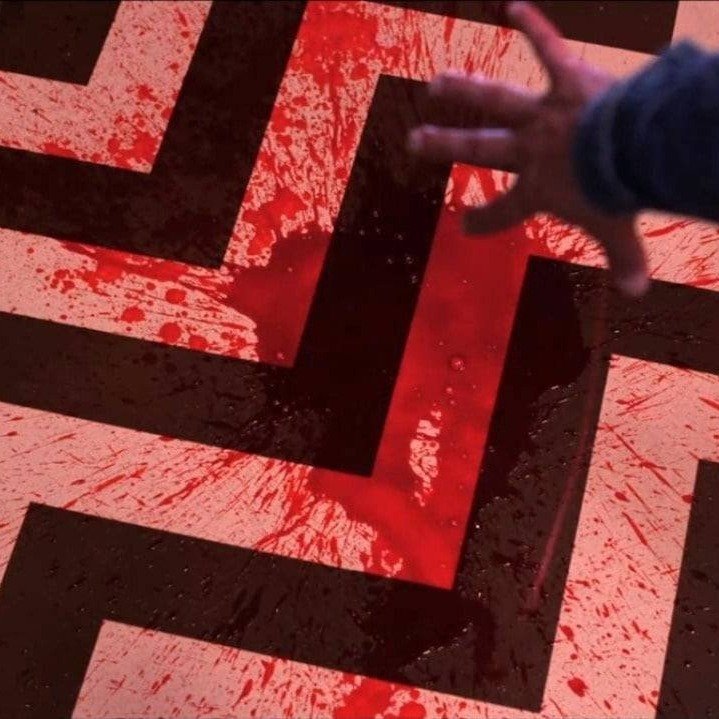

Fire Walk With Me (1992), initially rejected by audiences and critics, has since become the spiritual core of the entire saga. Where the original series relied on mystery, whimsy, and soap opera surrealism, the film plunges into Laura Palmer’s lived horror. By stripping away the distance of investigation and replacing it with intimate subjectivity, Lynch forces viewers to confront the pain buried beneath the quirky facade of Twin Peaks. Sheryl Lee’s performance is volcanic, revealing Laura not as an icon or puzzle but as a young woman fighting forces, internal and external, beyond comprehension. Her final scream in the Red Room becomes a cry for all victims who are unseen or unheard. The film reframes the entire mythology, the supernatural elements are not escapist fantasy but metaphors for generational trauma, cycles of abuse, and the invisible violence that exists in seemingly idyllic spaces.

If Fire Walk With Me is the emotional nucleus, The Return (2017) is the cosmic expansion. Spanning eighteen uncompromising hours, it is less a continuation of a television series than a wide open dream experiment, part epic, part elegy, part metaphysical puzzle. Lynch refuses nostalgia, instead breaking apart the familiar world of Twin Peaks and reassembling it into something disorienting and mournful. Agent Dale Cooper, once the embodiment of optimism and intuition, becomes fragmented across dimensions, the comatose Dougie Jones, the dark doppelgänger Mr. C, and a version of Cooper who ultimately crosses into another reality. The Return suggests that heroism, like identity, is unstable and fractured.

The series challenges our understanding of narrative closure. Episode 8, with its atomic bomb creation myth and haunting experimental imagery, recontextualizes the entire Lynchian cosmology as a struggle between cosmic forces unleashed by humanity’s own destructive tendencies. Meanwhile, the quieter moments, conversations in diners, sweeping floors, long stretches of silence, emphasize the passage of time and the fragility of memory. Twin Peaks is no longer a fixed place but a shifting reflection of loss and longing.

The final scene of The Return ties back to Fire Walk With Me in a devastating loop, Cooper and a parallel version of Laura, now Carrie Page, reach a familiar house that no longer recognizes them. Their identities dissolve into uncertainty, ending with Laura’s soul piercing scream once again rupturing the fabric of reality. It is the same scream that defined Fire Walk With Me, but now echoed across universes, suggesting trauma not as a closed story but as a reverberation.

Together, these works form a vast, aching meditation on the nature of suffering and the impossibility of returning home unchanged. Lynch crafts not answers but emotional truths, leaving us suspended in a dream where beauty and terror coexist. Twin Peaks does not end, it haunts.

Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive, and Inland Empire, The Labyrinth Years

Lynch’s late 1990s and early 2000s films form a trilogy of identity dissolution and narrative breakdown.

Lost Highway (1997) fractured storytelling, presenting a looping narrative that folds in on itself like a Möbius strip, challenging viewers to question who is dreaming whom.

Then came Mulholland Drive (2001), initially conceived as a TV pilot, rejected, then reborn into a masterpiece. A noir dreamscape about Hollywood illusions, fractured identities, and the price of desire, it has been hailed by many critics as the greatest film of the 21st century.

Finally, Inland Empire (2006), a sprawling, self generating digital nightmare filmed without a traditional script. For some, it's Lynch at his most impenetrable, for others, it’s his most liberated, intuitive creation.

And then, silence. Lynch stepped away from feature filmmaking, leaving audiences suspended somewhere between dream and waking.

Meditation, Music, and Mystery

Beyond film, Lynch poured his energy into painting, sculpture, photography, and music. His work with longtime collaborator Angelo Badalamenti produced some of the most haunting musical atmospheres in cinema, moody jazz, haunting synths, lush ambient textures.

Lynch is also a devoted practitioner of Transcendental Meditation, crediting it with helping him access creativity and inner stillness. Through the David Lynch Foundation, he championed meditation as a tool for mental health and trauma recovery, especially among students and veterans.

In Memory, David Lynch (1946–2025)

In 2025, the world lost one of its most original artistic voices. Lynch passed away at 79, leaving behind a legacy that is as enigmatic as it is influential. He resisted interpretations, insisting that viewers find meaning for themselves. Yet he also offered solace:

“Stay true to yourself. Let your voice ring out, and don’t let anyone get in the way.”

From Eraserhead to Twin Peaks, Lynch did more than direct; he sculpted dreams, cracked open the subconscious, and taught us that mystery is not a puzzle to be solved but an experience to be cherished.

RIP to a dreamer, a disruptor, and a true artist.

Want to experience Lynch for yourself? Start with,

Blue Velvet (1986), Suburbia meets the abyss, Hitchcock filtered through Kafka.

Mulholland Drive (2001), Hollywood noir unravelled into a gorgeous, devastating dream.

Twin Peaks, The Return (2017), perhaps the boldest television ever made.

By Jake James Beach

Founder- The Deep Dive Society

If you’ve enjoyed this exploration, we’d love to welcome you back to the Deepdive Society. Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media to stay connected, join the conversation and help build a community dedicated to curiosity, reflection and the art of looking deeper. Together, we can shape a society committed to the Deep dive mission.