Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Images, Ideas, and Indelible Cinema

by Jake James Beach — Founder of The Deep Dive Society

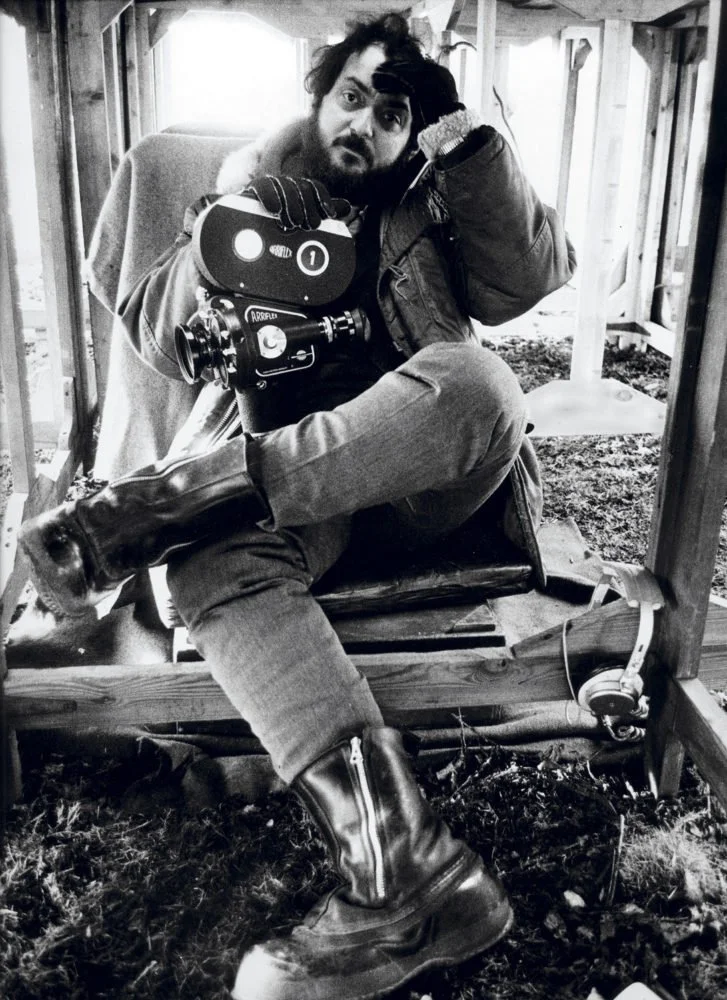

A black and white photograph of filmmaker Stanley Kubrick sitting casually on a makeshift wooden structure, holding an Arriflex camera in his lap.

Stanley Kubrick stands as a towering figure in cinematic history, his name synonymous with an uncompromising artistic vision that has left an indelible mark on the medium. Across nearly five decades, Kubrick’s films shattered conventions, stirred debate, and redefined what audiences could expect from the silver screen. Renowned for his relentless pursuit of perfection and his refusal to yield to industry pressures, Kubrick constructed works that interrogated the most profound moral, metaphysical, and political dilemmas of the twentieth century. Chronicling Kubrick’s career is, in essence, tracing the evolution of an outsider who revolutionised Hollywood from its periphery. He remains, by every measure, a visionary who not only forged his own path but also irrevocably altered the landscape of cinema.

Stanley Kubrick in the 1950s, during his time as a photographer for Look magazine

Stanley Kubrick was born on July 26, 1928, in the Bronx, New York, the son of a physician and a homemaker. His early years gave little indication of the legend he would become. Kubrick was neither an academic standout nor a social butterfly. Yet, from a young age, he harboured an intense inner world and a keen visual curiosity. That curiosity found its outlet at age 13, when his father gifted him a Graflex camera in hopes of lifting his son's spirits. The camera did more than that: it ignited a passion that would chart the course of Kubrick’s life.

By the age of 17, Kubrick was selling photographs to Look, a leading publication. His images stood out for their cinematic flair—dynamic framing, moody lighting, and a knack for seizing the telling gesture. Kubrick quickly secured a position as a full-time staff photographer, a role that became his proper education. Roaming New York with his camera, he gained a front-row seat to the metropolis’s human drama and honed the narrative instincts that would later define his filmmaking.

Kubrick’s photographic essays—documenting boxers in gritty gyms, jazz musicians immersed in their art, couples in smoky cafés, and everyday New Yorkers navigating city life—revealed an artist attuned to both surface and hidden depths. This apprenticeship in observation sharpened his ability to discern the moments where façade gave way to truth. Yet, as his eye matured, so did his ambitions. Still images, he realized, could only go so far; capturing the rhythm and momentum of life demanded a new medium. The lure of motion pictures soon proved irresistible.

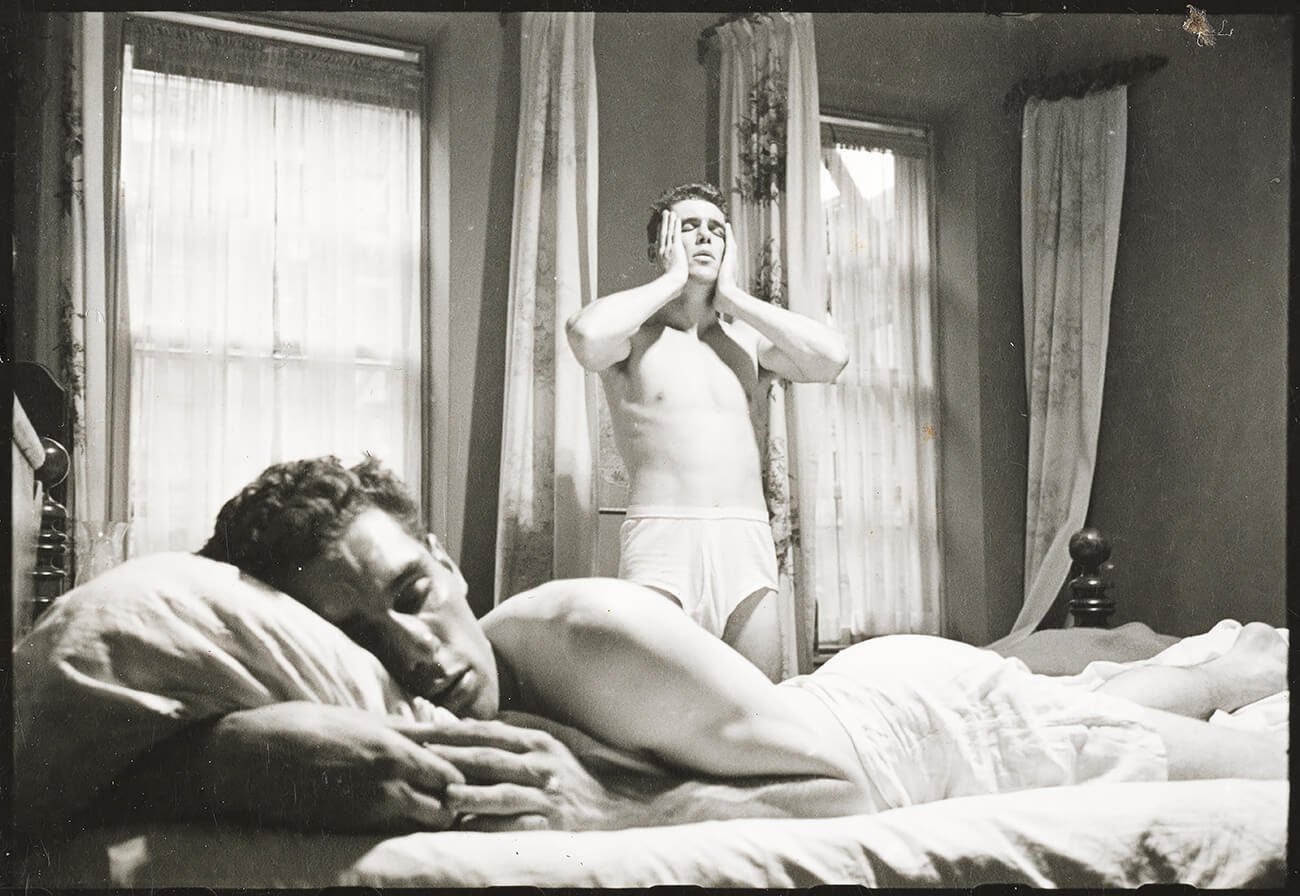

Stanley Kubrick for Look Magazine. Life and Love on the New York City Subway. 1947. © Museum of the City of New York. The LOOK Collection

Stanley Kubrick for Look Magazine. Life and Love on the New York City Subway. 1947. © Museum of the City of New York. The LOOK Collection

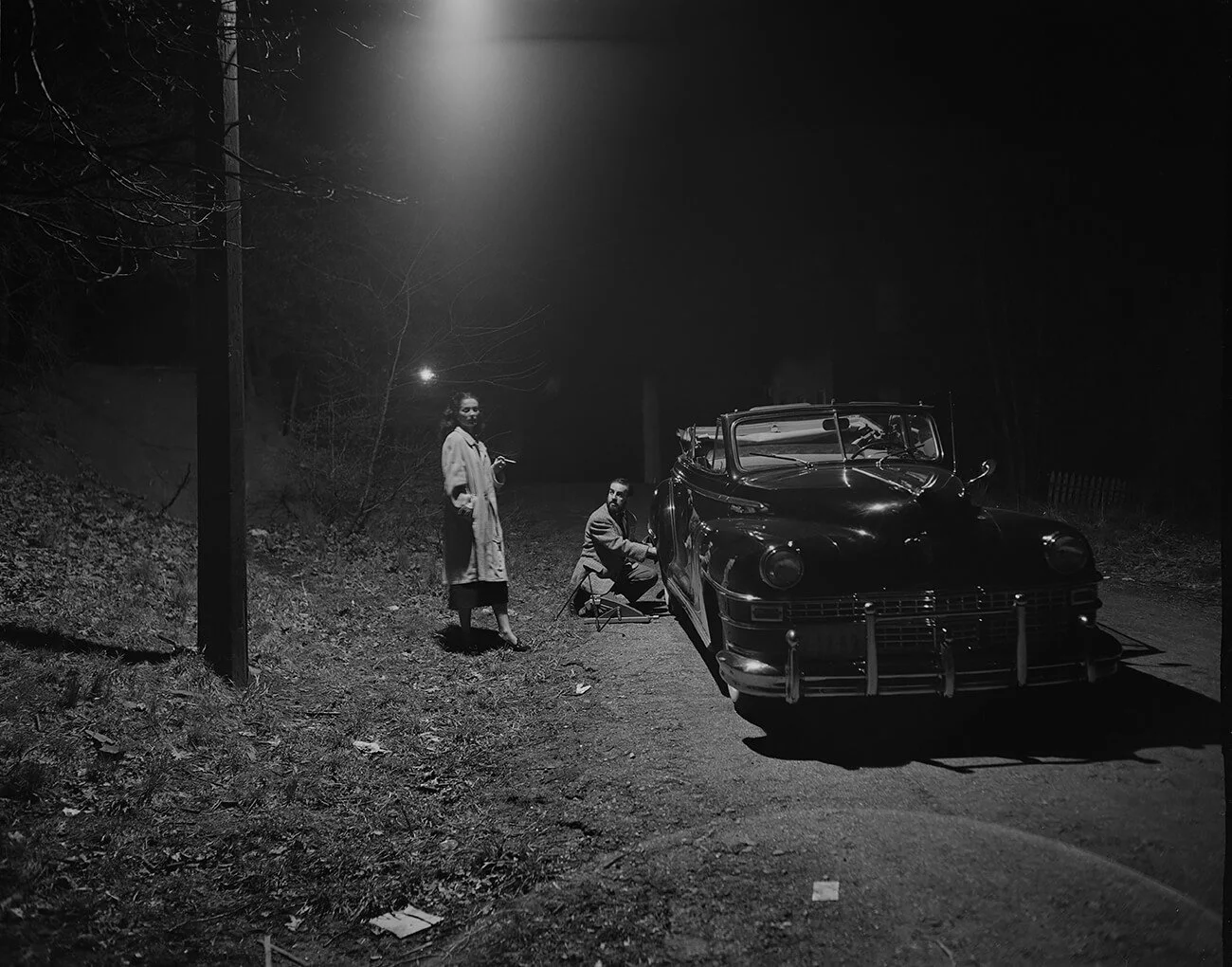

Stanley Kubrick for Look Magazine. Walter Cartier, Prizefighter of Greenwich Village. 1949. © Museum of the City of New York. The LOOK Collection

Stanley Kubrick for Look Magazine. Walter Cartier, Prizefighter of Greenwich Village. 1949. © Museum of the City of New York. The LOOK Collection.

Stanley Kubrick for Look Magazine. Show Girl. 1949. © Museum of the City of New York. The LOOK Collection

From the Streets to the Screen: The Documentary Years

Kubrick’s journey into cinema began with a series of self-financed documentaries. His debut, Day of the Fight (1951), trailed middleweight boxer Walter Cartier through the tension of an eventful match day. The film’s signature techniques, tracking shots, dramatic lighting, and a fascination with ritual became hallmarks of Kubrick’s later masterpieces. Though it saw only modest distribution, the project’s success emboldened Kubrick to press further into filmmaking.

He followed with two more documentaries: Flying Padre (1951), spotlighting a priest who crisscrossed rural New Mexico by plane, and The Seafarers (1953), a union-sponsored look at maritime life. Though these works are seldom screened today, they showcase Kubrick’s early gifts: a meticulous visual sense, a preoccupation with institutions, and a journalist’s nose for irony and contradiction.

Still, the documentary form could only contain Kubrick’s ambitions for so long. Eager for narrative command to shape not just reality but possibility, he took the bold leap into feature filmmaking while still in his early twenties.

The Apprenticeship of a Director: Early Features

Kubrick’s first forays into narrative cinema, Fear and Desire (1953) and Killer’s Kiss (1955), were produced on shoestring budgets, with funds scraped together from family and friends, borrowed gear, and skeletal crews. Though Kubrick would later dismiss Fear and Desire as a “childish exercise,” the film’s anti-war surrealism foreshadowed the hallmarks of his later work: alienated characters, moral gray zones, and a relentless questioning of war’s logic.

Killer’s Kiss, set amid the shadows and alleys of New York, showcased Kubrick’s growing command of visual storytelling. He rendered the city with a haunting lyricism of deserted avenues, towering facades, and doorways that seemed to beckon toward another reality. The film’s arresting style convinced United Artists to back Kubrick’s first major feature: The Killing (1956).

The Killing, Kubrick’s talent crystallised. The film, with meticulously structured heist told through fractured timelines and shifting viewpoints, announced his technical mastery and narrative daring. Though it failed to ignite the box office, The Killing quickly gained a reputation in Hollywood circles. Kubrick, still in his twenties, was hailed as a wunderkind.

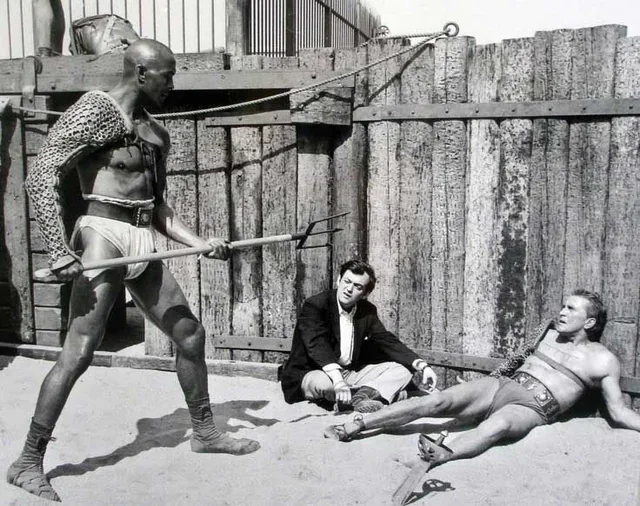

Kubrick’s next project, Paths of Glory (1957), starred Kirk Douglas and endures as one of cinema’s most searing anti-war statements, a blistering critique of military bureaucracy and moral cowardice among officers. The film’s iconic tracking shots through the mud-slicked trenches became a benchmark of cinematic bravura. So impressed was Douglas by Kubrick’s command that he pressed for the young director to helm Spartacus (1960).

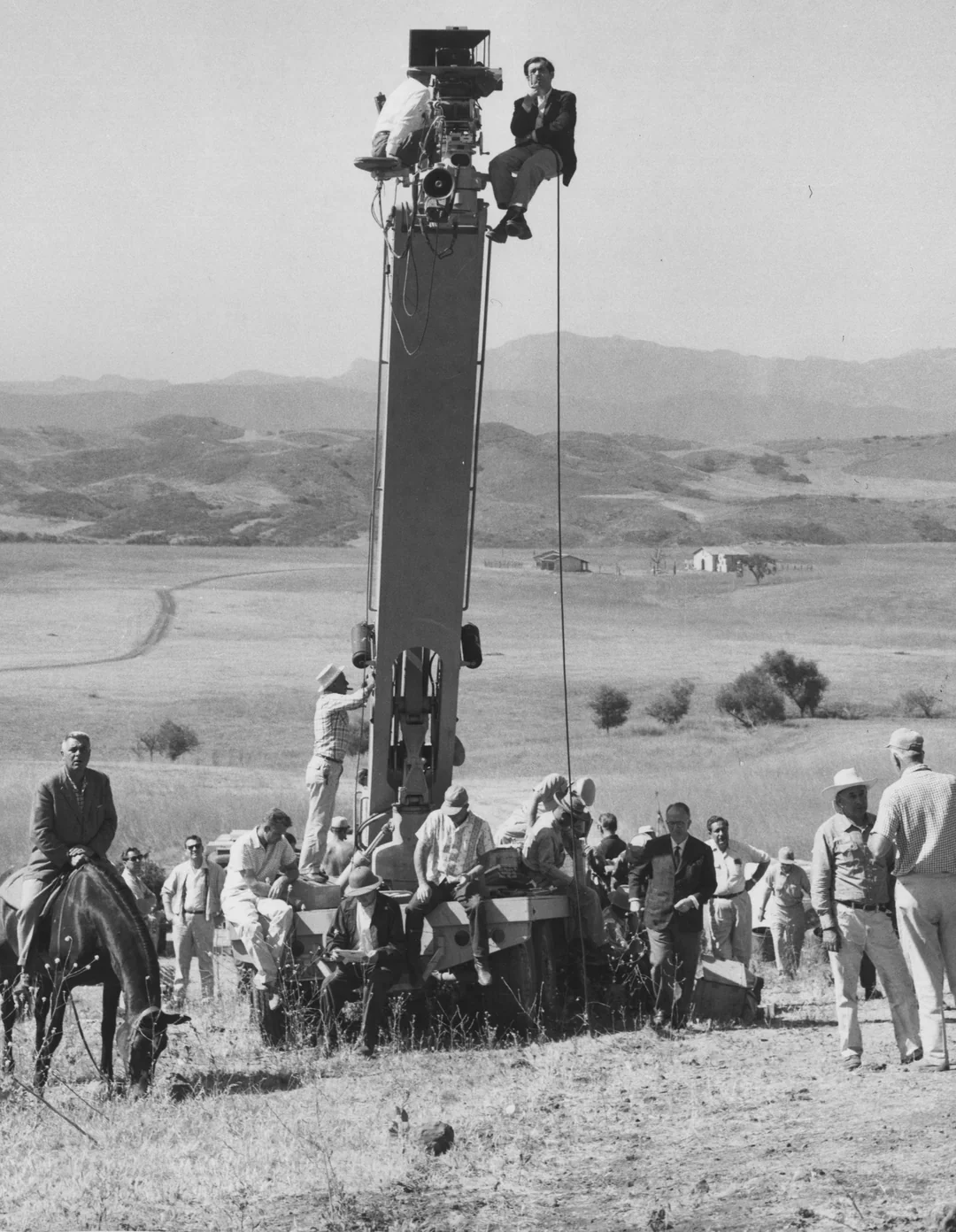

Hollywood Clash: Spartacus and Its Aftermath

"Spartacus" marked Kubrick’s lone foray into the traditional studio system, an experience that left the director both triumphant and disillusioned. Thrust into a sprawling production with a star-studded, sometimes unruly cast and forced to direct from a screenplay not his own, Kubrick navigated a minefield of clashing egos and Hollywood bureaucracy. The film became a blockbuster, collecting Academy Awards and box-office glory, but the victory rang hollow. Kubrick, hemmed in by studio interference and creative compromises, bristled at the limitations imposed by the system.

Yet, in the shadows of frustration, Kubrick found leverage. The runaway success of "Spartacus" became his bargaining chip, granting him unprecedented artistic control in the future. Determined never to cede his vision again, Kubrick decamped to England, where he could orchestrate every detail of his productions in near-total seclusion. From this self-imposed exile, he would assemble a body of work that forever changed the language of film.

The Kubrick Method: Obsession Becomes Art

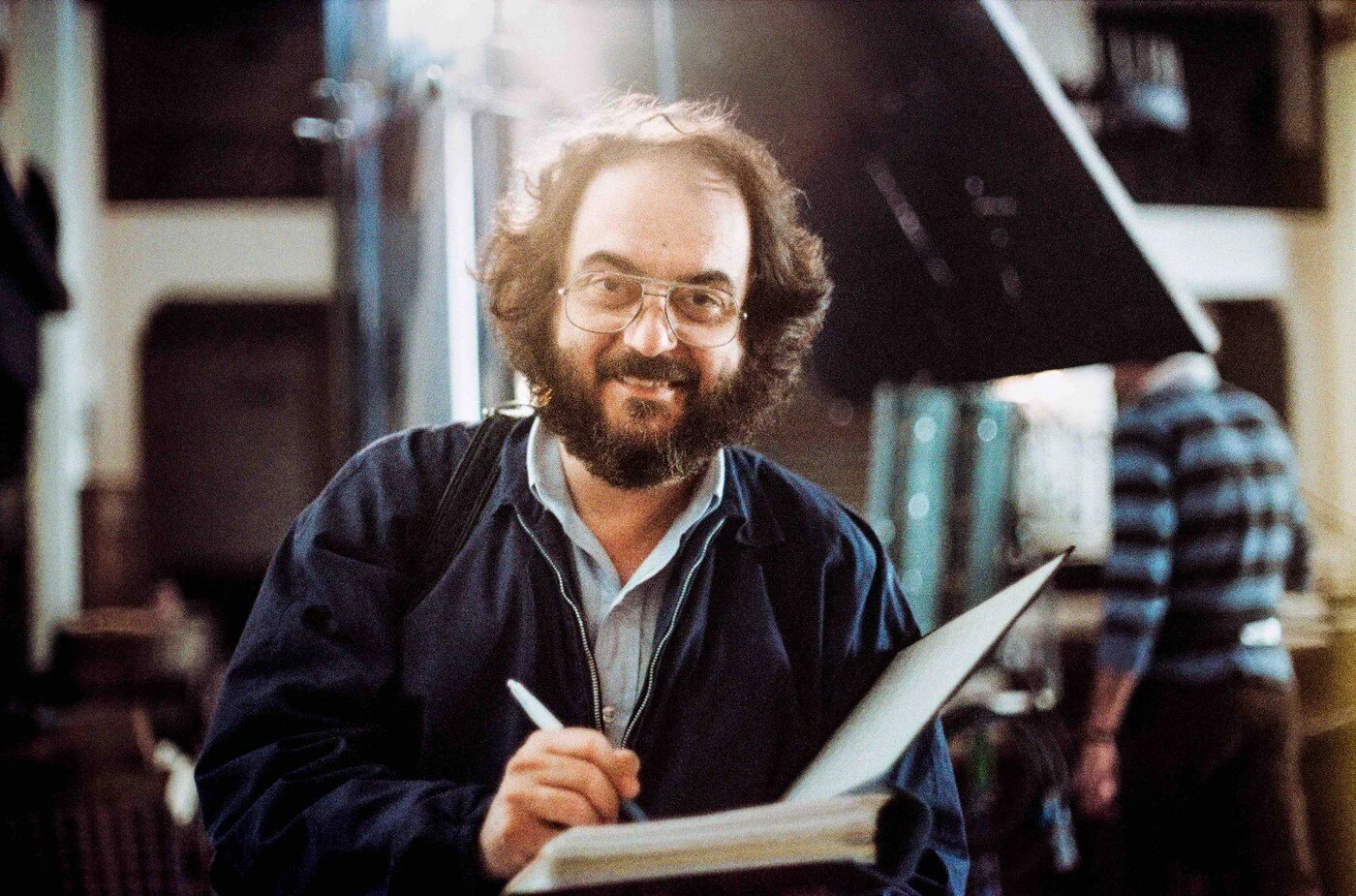

To understand the films that followed, one must first decode Kubrick’s legendary process, a regime of research, repetition, and relentless innovation. The director’s method was forensic in its thoroughness: he devoured stacks of books before penning a script, insisted on take after take until performances reached an almost hypnotic exactitude, and pushed the boundaries of film technology with each new project.

Ambiguity was Kubrick’s signature. He posed questions, rarely answered, and shunned interviews, preferring to let his films provoke debate in his absence. Though stories of his perfectionism veered into myth, sometimes painted as tyrannical, collaborators often described a director whose single-minded drive inspired as much respect as frustration. On set, Kubrick was less a Hollywood mogul than an obsessive artist, agonizing over every prop, every shaft of light, every note of the score. The result: films that felt meticulously crafted, down to the last frame.

Dr. Strangelove: Satire at the Brink

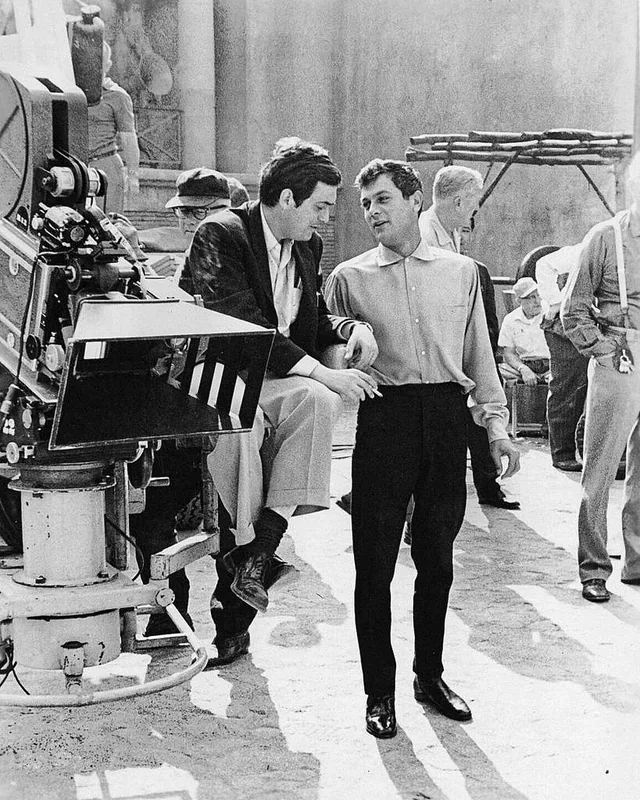

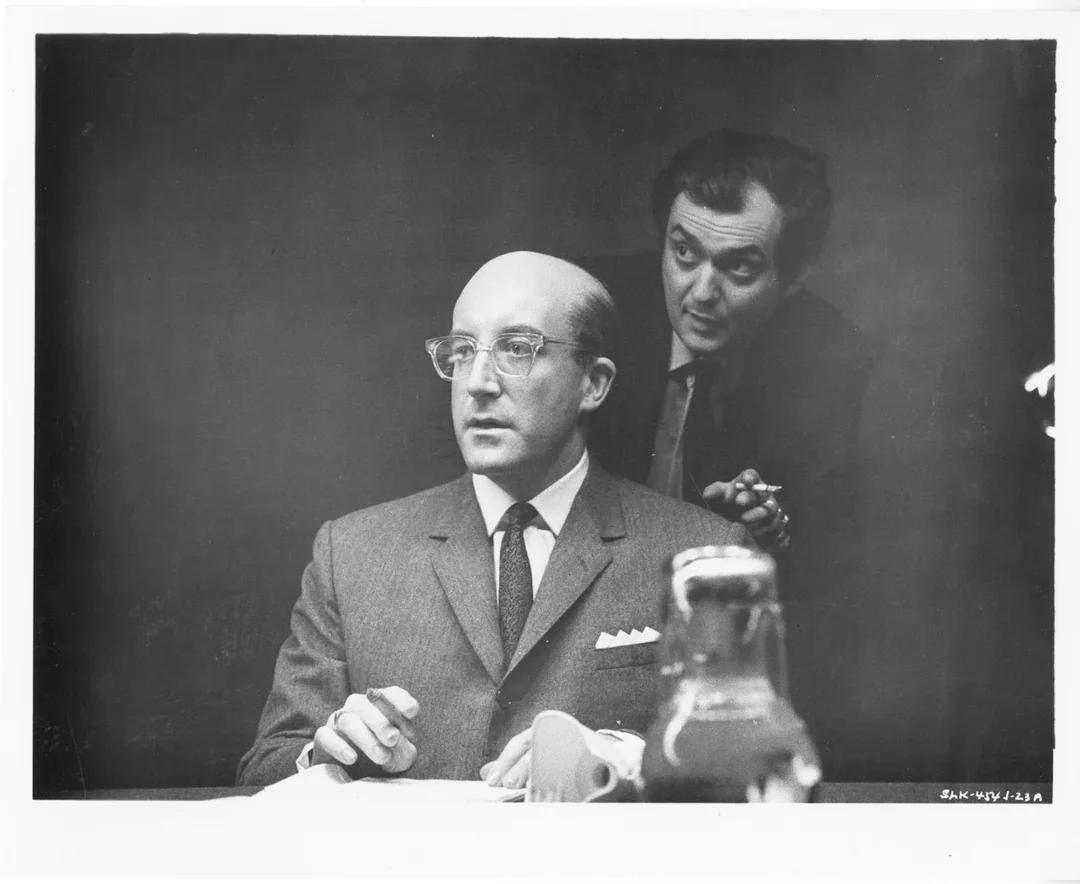

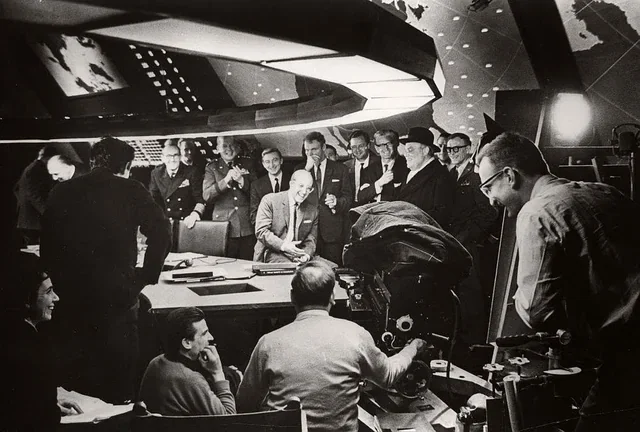

Kubrick’s reinvention began with a detonation, "Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb" (1964). What started as a grim meditation on nuclear annihilation mutated, under Kubrick’s scalpel, into perhaps the sharpest political satire ever committed to film.

Peter Sellers, inhabiting multiple roles, anchored a cast of buffoonish generals and hapless politicians whose absurdities felt all too plausible. The film’s chilling humor and surreal logic captured the existential dread of the Cold War era, making audiences laugh even as they peered into the abyss. Overnight, "Dr. Strangelove" entered the canon not as a singular statement, but as a masterclass in balancing irony, terror, and wit. With it, Kubrick proved he could orchestrate multiple tones at once, crafting cinema that was both provocation and entertainment.

2001: A Space Odyssey The Medium Transformed

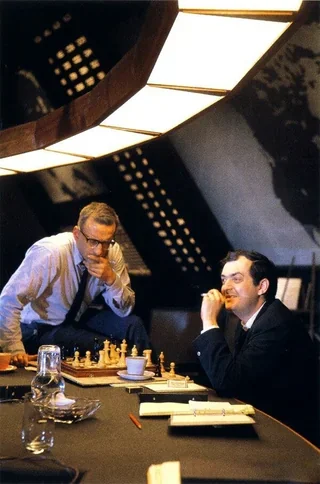

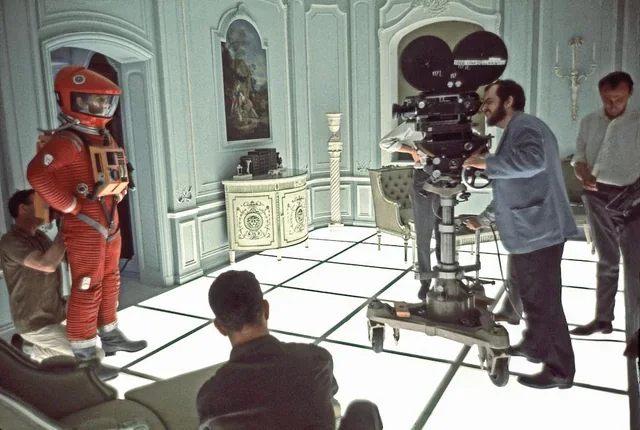

When "2001: A Space Odyssey" (1968) premiered, it didn’t just raise the bar for science fiction; it reinvented cinematic possibility. Partnering with visionary author Arthur C. Clarke, Kubrick aimed not for spectacle but for transcendence. The film’s epic sweep spanning aeons, eschewing exposition for pure visual storytelling, confounded critics but mesmerized audiences willing to surrender to its mysteries.

HAL 9000, the implacable AI whose polite menace became legendary, posed questions about technology and consciousness that still resonate in the digital age. "2001" divided the critical establishment at first, but quickly became a touchstone for filmmakers and dreamers alike. Today, it is not merely a classic; it is cinema’s grandest riddle, a work whose influence is as infinite as the cosmos it imagines.

A Clockwork Orange: Shock and Censure

Kubrick’s adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s "A Clockwork Orange" (1971) detonated like a cultural grenade. The film’s dystopian nightmare, where violence is both condemned and fetishized, forced viewers to confront the boundaries of free will and social control. Malcolm McDowell’s electric turn as Alex, the gleefully depraved protagonist, became instantly iconic.

Kubrick’s fusion of baroque music, lurid visuals, and balletic brutality created a world at once mesmerizing and repulsive. The film drew fire almost immediately: British tabloids blamed it for a spate of copycat crimes, and the ensuing controversy grew so heated that Kubrick himself pulled the film from UK cinemas. The ban would remain until after his death, cementing the film’s reputation as both a masterpiece and a lightning rod.

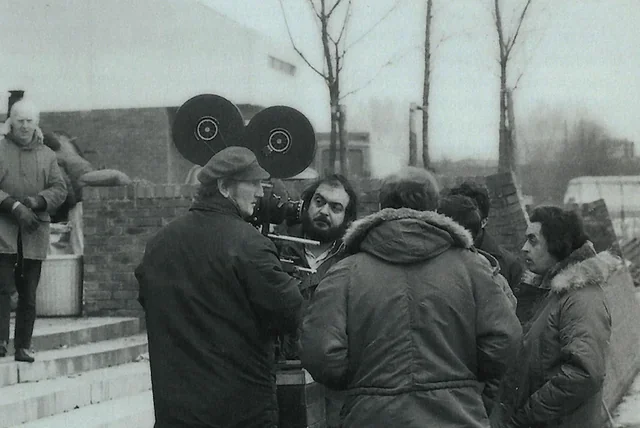

Stanley Kubrick filming A Clockwork Orange on Binsey Walk 1970

Barry Lyndon: Cinema as Canvas

With "Barry Lyndon" (1975), Kubrick traded dystopian violence for the lush pastures of 18th-century Europe, adapting Thackeray’s tale of ambition and downfall. The film’s technical feats became legend: Kubrick famously shot entire scenes by candlelight, using NASA-developed lenses to capture the era’s authentic glow. The result was a visual feast, each frame composed like a painting, each shot imbued with the melancholy of history.

Dismissed at first for its stately pace, "Barry Lyndon" has since been reclaimed by critics as one of Kubrick’s crowning achievements. It is a meditation on fate, class, and the inexorable passage of time a film that lingers, quietly, in the mind’s eye long after the credits roll.

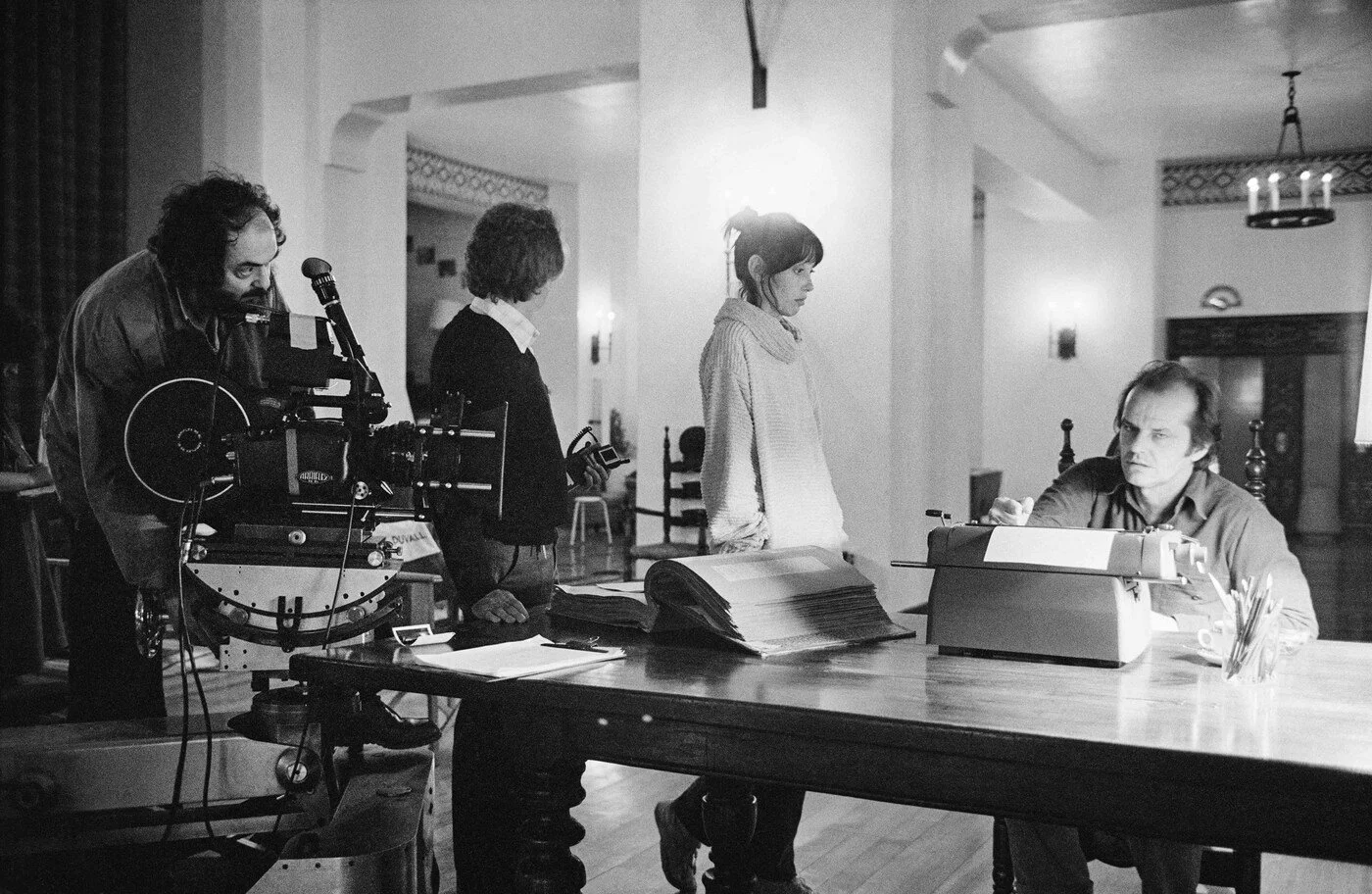

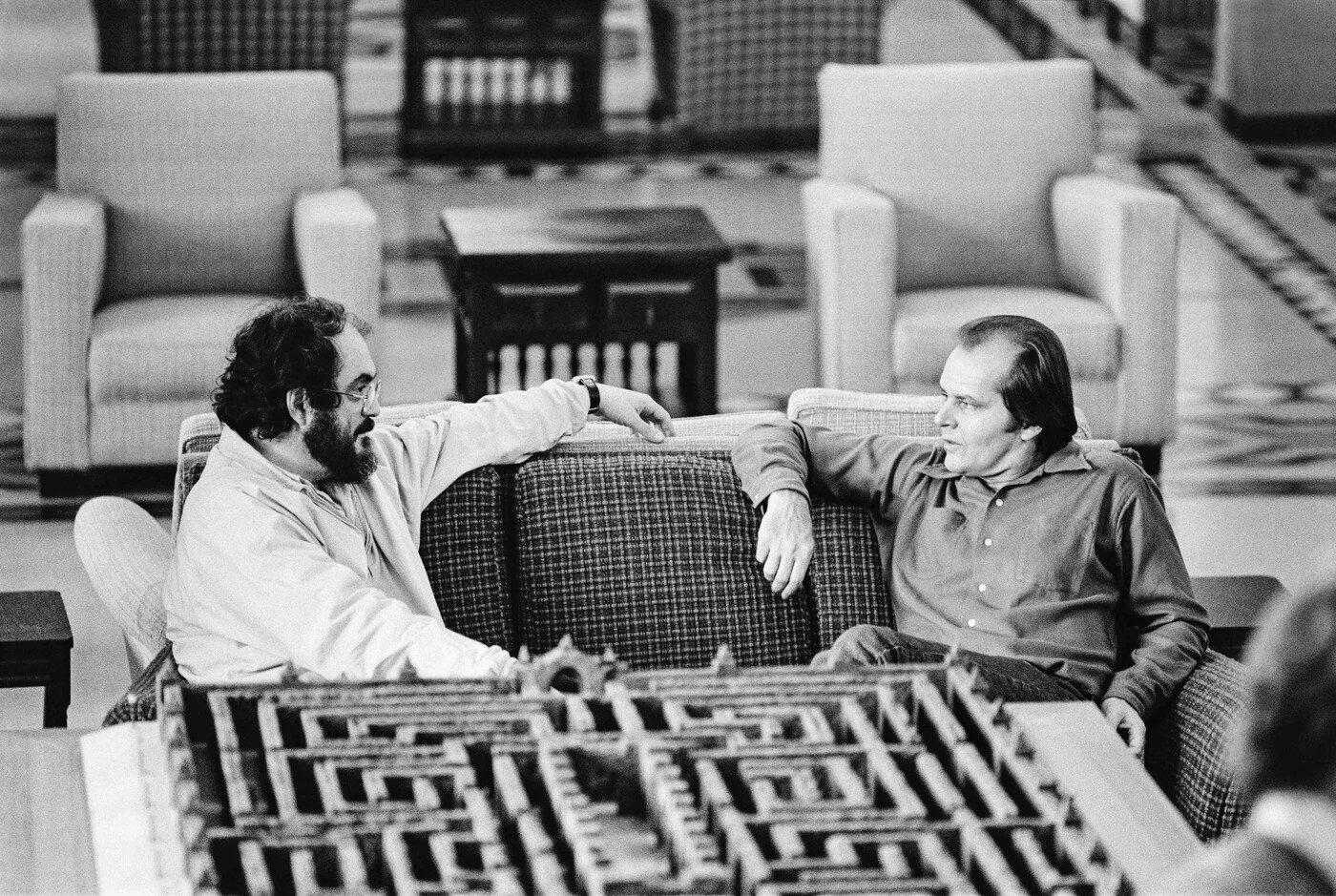

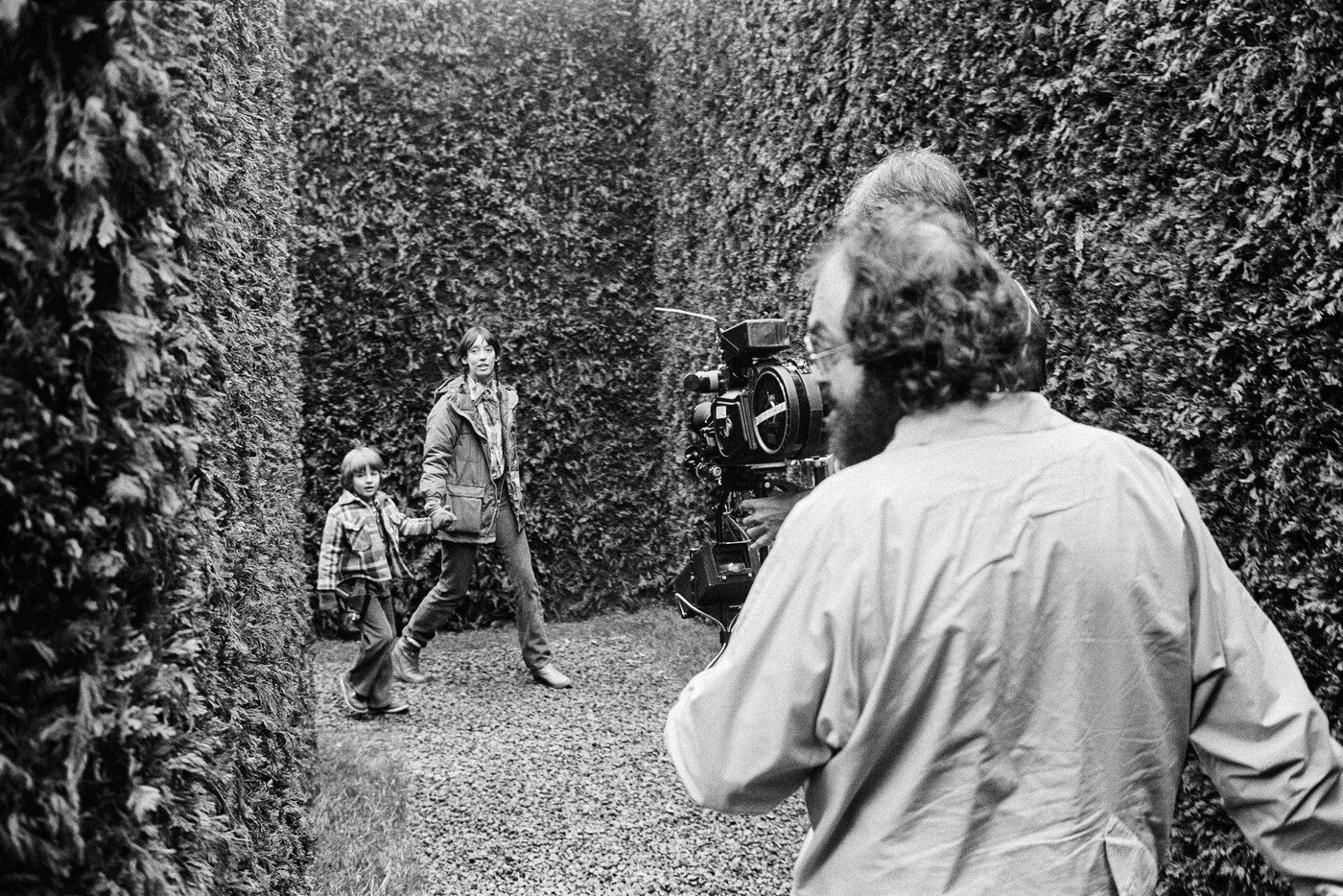

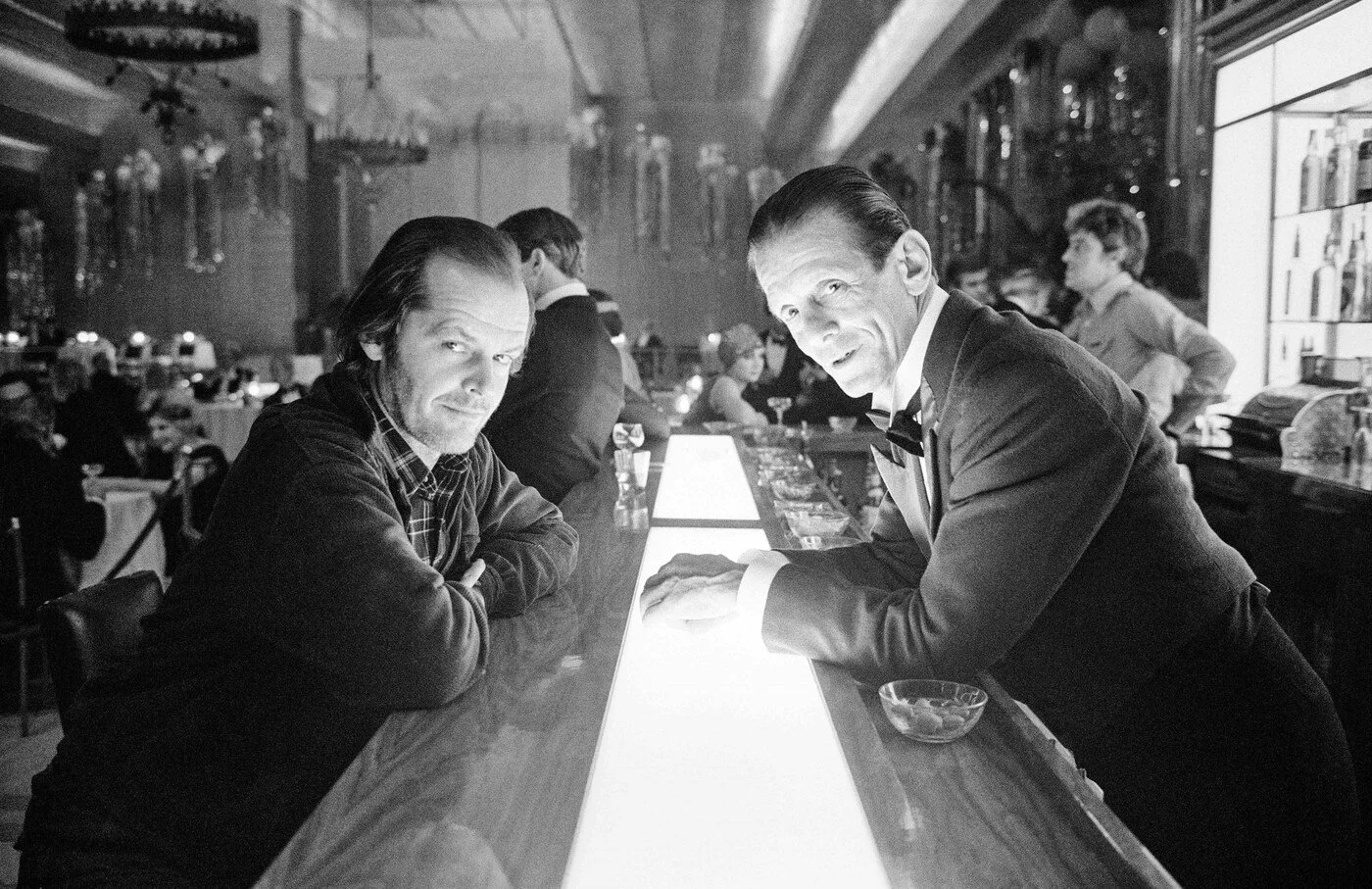

The Shining: Fear in the Corridors

Kubrick’s foray into horror arrived in 1980 with "The Shining," an adaptation of Stephen King’s bestseller. The author disavowed the film, but audiences and critics have since enshrined it as a genre-defining classic. Rather than cheap thrills, Kubrick conjured dread through architecture and atmosphere, transforming the Overlook Hotel into a maze of psychological peril.

Jack Nicholson’s iconic unraveling as Jack Torrance, Shelley Duvall’s palpable terror, and young Danny’s haunted visions combined to create a cinematic nightmare. Kubrick’s pioneering use of the Steadicam—tracking Danny’s tricycle as it echoes through empty hallways set a new standard for visual storytelling. For Kubrick, horror was not the monster at the door, but the creeping sense that reality itself could not be trusted.

Full Metal Jacket: War’s Assembly Line

"Full Metal Jacket" (1987) saw Kubrick return to the crucible of war, dissecting the Vietnam conflict with clinical detachment. The film’s split structure, boot camp, half battlefield, revealed the brutal alchemy of military indoctrination. R. Lee Ermey’s turn as the sadistic drill instructor became a pop-culture archetype, his tirades echoing through cinema history.

As the narrative shifts to the bombed-out streets of Hue, Kubrick’s camera captures not heroism, but the machinery of violence: soldiers stripped of identity, war as a process that grinds down the soul. If "Paths of Glory" exposed the insanity of command, "Full Metal Jacket" laid bare the methods by which ordinary men are remade for carnage. Kubrick’s examination is pitiless, but no less than riveting.

‘Stanley never said which part I was auditioning for’ … Matthew Modine as Joker. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Stanley Kubrick working on set in Beckton. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Vincent D’Onofrio, Matthew Modine and drill sergeant R Lee Ermey in Full Metal Jacket. Photograph: Everett/Rex/Shutterstock

Eyes Wide Shut: The Final Enigma

Kubrick’s swan song, "Eyes Wide Shut" (1999), remains a riddle wrapped in velvet. Adapting Arthur Schnitzler’s tale of marital longing and secret societies, Kubrick cast Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman as a couple spiraling through jealousy, erotic fantasy, and dreamlike intrigue.

The film is a fevered blend of psychological thriller and sensual reverie, each scene bathed in a surreal glow that teeters on the brink of reality and hallucination. Kubrick labored over the production for more than a year, sculpting a world where the boundaries of desire and identity blur with every shadowed corridor.

Tragically, Kubrick died just days after delivering his final cut. Debate still swirls around "Eyes Wide Shut," its meaning, its tone, its place in the director’s legacy. What endures is its haunting ambiguity: a parting gift from cinema’s most elusive visionary.

Kubrick’s Legacy: Cinema’s Relentless Architect

Stanley Kubrick’s cinematic footprint is paradoxically modest in quantity, colossal in impact. His dozen or so films are not merely disparate stories, but chapters in a single, searching worldview: a distrust of authority, an obsession with systems, a fascination with the razor’s edge between order and chaos. He confronted uncomfortable truths with technical brilliance and an unblinking eye, reshaping what film could accomplish.

A genre chameleon, Kubrick leapfrogged from war to sci-fi, horror to satire, period drama to erotic mystery. Yet every film bore his unmistakable signature: precision, philosophical heft, and a cool detachment that demanded audiences engage, interpret, and reflect. His innovations in visual storytelling and technology set new standards that ripple through the industry to this day.

The Kubrick effect is everywhere. A-list directors Christopher Nolan, Paul Thomas Anderson, David Fincher, and Denis Villeneuve trace their cinematic DNA to his influence. His films are dissected in classrooms, debated by critics, and worshipped by cinephiles, while his unrealized projects Napoleon, A.I., and Aryan Papers have become the stuff of legend.

What set Kubrick apart was his unyielding control; he didn’t just direct movies, he conjured entire worlds. Each was immersive, unsettling, and meticulously crafted to endure. In an industry built on compromise, Kubrick stood alone: a one-man vanguard for artistic autonomy.

The Quiet Radical.

For all his renown, Kubrick kept his life private, choosing an English manor over Hollywood’s glare, surrounding himself with family, books, and editing gear. He let the myths swirl, but the reality was simpler: he prized craft above celebrity, substance over spectacle. Kubrick’s legacy isn’t defined by eccentricity, but by conviction. He made films not for the box office, but for posterity. With each project, he argued frame by frame that cinema could be as serious, searching, and transcendent as any other art form.

What endures is a body of work that dares to stare into the world’s shadowy corners. Kubrick didn’t just push boundaries; he redrew the map of what movies can be.