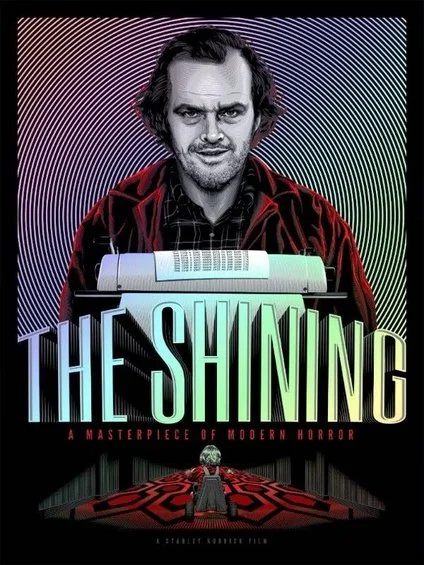

Why The Shining Still Haunts Audiences 45 Years Later

Forty-five years after its release, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining remains one of the most confounding, hypnotic, and enduring films in cinema history. It is a movie that doesn’t merely survive rewatching it demands it. Scholars unpack it. Fans argue over it. Filmmakers imitate it. And general audiences, even those encountering it for the first time, emerge with the same uneasy sensation: something in this film is watching them back.

Kubrick’s adaptation of Stephen King’s 1977 novel is famous for its departures from the source material. Where King wrote a supernatural ghost story about addiction and redemption, Kubrick created a stark, icy meditation on madness, isolation, violence, and the haunted architecture of America itself. The result is something uniquely unsettling: a horror film that refuses to behave like one.

As new generations discover The Shining—through streaming, Halloween rewatches, college classes, or the internet’s ever-growing library of fan theories the question resurfaces: What makes this film so disturbingly timeless? Why has this story, set in an empty hotel with just three primary characters, grown into a cultural monolith?

To understand The Shining’s longevity, one must look at the film through the very lenses Kubrick used to construct it: psychology, spatial design, symbolism, American history, and the pressures of family and masculinity. What emerges is a multi-layered text—one whose power comes not from what it resolves, but from what it refuses to explain.

A Hotel Designed to Unnerve: Architecture as Psychological Weapon

One of Kubrick’s most ingenious decisions was to treat the Overlook Hotel not as a backdrop but as an active participant. The building shifts. It contradicts itself. It contains windows that can’t exist and hallways that should lead nowhere. A character turns a corner, and the audience instinctively feels something is wrong, even if they can’t articulate why.

These spatial impossibilities aren’t accidents. They’re psychological tactics.

Film scholars often describe the Overlook as a representation of the human mind. Its endless hallways become memory corridors; its locked rooms symbolize repressed trauma; its patterned carpets and wallpaper echo obsessive thought loops. The result is a space that feels almost predatory an interior world capable of swallowing its inhabitants.

It is in this environment that Jack Torrance, struggling writer and increasingly unstable father, begins to unravel. The more time he spends in the hotel, the more he resembles it: repetitive, contradictory, menacing.

Jack doesn’t just get lost in the Overlook.

He becomes part of it.

America’s Buried Violence and the Ghost That Isn’t a Ghost

One of the film’s most-debated details—the Overlook being built on an “Indian burial ground”—is often misunderstood as a throwaway horror convention. But Kubrick uses it as a thematic anchor. It suggests the hotel is built upon layers of erased or ignored suffering, much like the country itself.

This reframes the film’s conclusion. When the photograph reveals Jack in a 1921 ballroom celebration, it hints not at literal reincarnation but at repetition cycles of exploitation, dominance, and violence repeating through history. Jack becomes another caretaker in a long lineage of men who perform brutality under the guise of authority.

In this reading, the ghosts of The Shining are not supernatural beings.

They are historical patterns.

The film’s most chilling line

“You’ve always been the caretaker.”

functions less as a haunting and more as a diagnosis.

Masculinity in Freefall: The Horror of Creative Failure

At its psychological core, The Shining is the story of a man who fears he has failed. Jack Torrance arrives at the Overlook with the dream of writing a novel and reclaiming a version of himself he believes he has lost. However, instead of producing art, he produces repetition: page after page of the infamous line “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.”

The manuscript represents more than madness it symbolizes the collapse of male identity under pressure. Jack believes he deserves greatness. When greatness does not come, he turns on the people closest to him.

Wendy becomes the scapegoat.

Danny becomes the burden.

The hotel becomes the excuse.

In this light, The Shining is as much about the fragility of patriarchal expectations as it is about hauntings.

The Question That Never Gets Answered: What’s Real? What Isn’t?

One of Kubrick’s most controversial choices was to strip King’s novel of its clear supernatural logic. Instead, the film exists in a state of perpetual ambiguity. Are the ghosts real? Or is Jack hallucinating under stress, isolation, and alcoholism?

Kubrick offers no definitive answer.

This uncertainty places The Shining within the literary tradition of “the fantastic,” where narratives remain suspended between rational and supernatural explanations. The elevator of blood could be a manifestation of trauma. The ghostly bartender may be Jack’s addiction speaking. The Grady twins might be Danny’s psychic projections.

The film’s refusal to resolve these interpretations is not a flaw.

It is its central power.

Scenes That Imprinted Themselves on Culture

Few films contain as many instantly recognizable moments as The Shining. Even people who have never seen the film can identify:

The torrent of blood spilling from the elevator

Danny’s tricycle gliding down patterned hallways

The whisper of “REDRUM”

The Grady twins inviting him to “come play”

Jack’s axe smashing through the bathroom door

“Here’s Johnny!”—now one of the most quoted lines in cinema

These scenes endure not because of shock value but because Kubrick frames them like recurring nightmares—cyclical, symbolic, and eerily calm.

Why The Shining Still Matters Today

The film’s longevity is rooted in its flexibility. The Shining can be read as:

A psychological case study

A critique of American history

A metaphor for addiction

A domestic horror about abuse

An exploration of creative paralysis

A surrealist dream-logic narrative

A symbolic text about power and repetition

In every interpretation, the film remains relevant. Isolation? Trauma? Violence? The pressure to produce? These are not just horror tropes they are contemporary realities.

Moreover, the film’s imagery has become part of the aesthetic language of horror itself. The Overlook carpet pattern appears on clothes, posters, and memes. Danny’s tricycle shot influenced generations of Steadicam technique. Even Kubrick’s color palette—blood red, icy blue, sickly gold—has become visual shorthand for unease.

The film doesn’t age.

It adapts.

A Final Image That Never Stops Speaking

The ending photograph remains one of cinema’s greatest mysteries. Jack, smiling in a perfectly framed 1921 ballroom portrait, looks contentfi nally at home in the cycle of history.

But the question lingers:

Did the hotel absorb him?

Did he reincarnate?

Or was he always destined to be there?

Kubrick’s refusal to clarify ensures the film’s afterlife.

The Overlook Hotel continues to expand in the imagination adding new wings, new interpretations, new corridors.

Conclusion: A Labyrinth Without an Exit

The Shining endures because it cannot be completed.

It is a riddle without a solution, a maze without a centre.

Each viewing reveals something new, something missed, something uncomfortable.

Kubrick crafted a film that doesn’t simply scare it reflects. It mirrors the viewer’s anxieties, cultural tensions, and historical shadows. Like the Overlook itself, the film feels alive.

And perhaps that is why it haunts us.

We never really leave.

We just return to the maze.

By Jake James Beach — Founder of The Deep Dive Society

Sources

Onay, Özge. Reading Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining Against the Backdrop of His Cinematic Expression. CINEJ Cinema Journal 12(1): 385-405, 2024. DOI: 10.5195/cinej.2024.621. Link cinej.pitt.edu

“A Dramaturgical Analysis of The Shining.” Senses of Cinema, Issue 95, 2020. Link sensesofcinema.com

Biotti, Gabriele. The Uncanny and the Ghostly Nature of the World in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980). Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature 43(4), 2019. PDF Link journals.umcs.pl

“Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining: An embodied film experience.” Academic Studies Press Blog, Oct. 2019 (Maarten Coëgnarts). Link Academic Studies Press

“The Shining: Horror Perfected” – article on film’s aesthetic & atmosphere. Arts@Michigan, Dec. 2019. Link artsatmichigan.umich.edu

“A Story Torn in Two: Revisiting The Shining.” Runestone Journal, 2023. Link runestonejournal.com